Walk through the quiet paths of Kew Gardens on a misty morning, and you’ll feel like you’re stepping into a living museum. The hedges are trimmed to perfection, the ornamental ponds reflect centuries-old statues, and every flower bed tells a story of taste, power, and artistry. These aren’t just parks. They’re time capsules shaped by kings, queens, botanists, and landscape artists who turned dirt and plants into statements of legacy.

What Makes a Garden Historic?

A historic landscaped garden isn’t just old. It’s a deliberate design that reflects the values, science, and aesthetics of its time. In London, these spaces were often created for the wealthy-nobles, merchants, and royalty-who used them to show off wealth, intellect, and control over nature. Unlike today’s public parks, which focus on recreation, historic gardens were meant to impress, inspire, and even educate.

Take the Georgian era (1714-1830). Gardens from this period were all about symmetry, order, and classical influence. Think straight avenues lined with lime trees, formal parterres, and statues of Roman gods. The design followed rules from ancient Rome and Greece, as if nature itself needed to be corrected to meet human ideals.

Then came the Victorian era (1837-1901), and everything changed. Gardens became more romantic, wilder, and packed with exotic plants brought back from colonies. Ferneries, glasshouses, and water features exploded in popularity. The rise of rail travel meant Londoners could visit these gardens on weekends. Suddenly, private estates like Chiswick House or Stowe became public attractions.

Five Landscaped Gardens That Define London’s Heritage

London has dozens of historic gardens, but five stand out as essential to understanding its garden heritage.

- Kew Gardens - Officially the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, this 300-acre site began as a royal pleasure garden in 1759. Today, it’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site with over 50,000 living plants. Its Palm House, built in 1848, was an engineering marvel-iron and glass forged into a greenhouse that could house tropical trees. Kew wasn’t just beautiful; it was a scientific hub. Botanists here cataloged species from India, Australia, and the Caribbean, shaping global plant knowledge.

- Chiswick House Gardens - Designed by William Kent in the 1730s, this is one of the earliest examples of the English landscape style. Kent moved away from rigid geometry and instead created rolling lawns, serpentine paths, and carefully placed follies-like the Temple of Venus-that looked like ruins from ancient times. It was a reaction against French formality. Here, nature was curated to look wild, even though every tree was planted by hand.

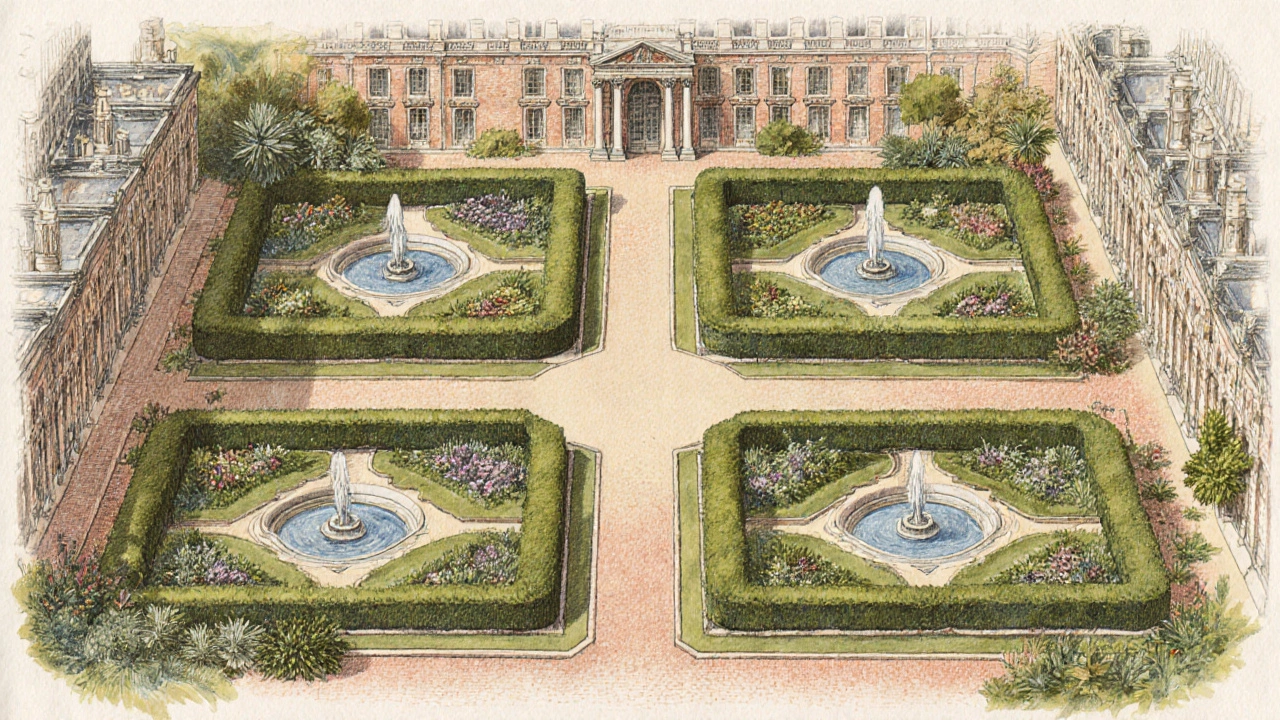

- Hampton Court Palace Gardens - These gardens were shaped by Henry VIII and later William III. The famous Privy Garden, restored in the 2000s, still uses the original 17th-century layout: four quadrants divided by paths, with topiary and fountains. The Great Fountain Garden, rebuilt in 2010, mimics the grandeur of Versailles but with English restraint. What’s unique here is the layering of styles-you can see Tudor, Baroque, and Victorian elements all in one place.

- St. James’s Park - London’s oldest royal park, dating back to 1532. Originally a marshy hunting ground, it was transformed into a formal garden under Charles II, then redesigned in the 1820s by John Nash into the sweeping lake-and-lawn layout we know today. The park’s ducks, pelicans, and views of Buckingham Palace make it feel like a postcard. But its design was political: wide vistas showed off royal power, and the park became a model for public green spaces across the city.

- Blenheim Palace Gardens - Technically just outside London in Oxfordshire, Blenheim is too important to leave out. Designed by Henry Wise and later Capability Brown, it’s a masterpiece of the English landscape movement. Brown’s genius was in making the garden feel boundless-using dips in the land, hidden walls, and carefully placed trees to hide boundaries. Visitors didn’t realize they were walking through a carefully controlled illusion.

Design Principles Behind the Beauty

These gardens didn’t just happen. They followed clear design philosophies.

The English Landscape Movement, led by figures like Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, rejected rigid symmetry. Instead, they favored natural-looking curves, open lawns, and strategically placed clumps of trees. Brown’s motto was to make gardens look like they’d always been there-even if he’d moved entire hills to get the effect.

Then there’s the picturesque style, popular in the late 1700s. Designers like Humphry Repton wanted gardens to look like paintings. They added viewpoints, framed vistas through arches, and even planted trees to mimic the brushstrokes of landscape artists like Claude Lorrain. Repton even published ‘Red Books’-before-and-after sketches showing how his designs would transform a property. These were the original mood boards.

And don’t forget the botanical purpose. Many gardens were also scientific collections. At Kew, plants were labeled with their Latin names and grouped by family. At the Chelsea Physic Garden (founded in 1673), medicinal herbs were grown for medical training. These weren’t just pretty-they were working labs.

How These Gardens Survived the Modern Age

After World War II, many historic gardens fell into neglect. Maintenance was expensive, and public interest shifted to sports fields and playgrounds. By the 1970s, Kew’s glasshouses were leaking, Chiswick’s statues were covered in moss, and Hampton Court’s fountains were dry.

The turning point came with heritage campaigns. In 1984, the Historic Gardens Foundation was formed. Volunteers, historians, and local councils began restoring what had been lost. At Kew, the Palm House got a £20 million renovation. At Chiswick, over 10,000 plants were replanted using 18th-century seed records. Today, these gardens are protected by law. Many are Grade I listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens-meaning any change must be approved by Historic England.

What keeps them alive now? Public support. Over 2 million people visit London’s historic gardens each year. Schools bring students for botany lessons. Artists sketch in the gardens. Couples take wedding photos under the same arches that once framed royalty. They’re not relics-they’re living spaces still shaping how Londoners connect with nature.

Visiting Today: What to Look For

If you’re planning a visit, don’t just walk through. Look closer.

- Check the curb lines-are they straight (Georgian) or curved (Brownian)?

- Look for follies-fake ruins, temples, or obelisks placed to create a sense of history.

- Notice the planting style. Are there exotic species like rhododendrons or camellias? That’s Victorian.

- Find the water features. A formal pond means 17th-century design. A meandering stream? Likely 19th-century.

- Read the plaques. Many gardens now have QR codes or information panels explaining the original designers and what was restored.

Visit in spring for the tulips at Hampton Court, or autumn for the fiery maples at Kew. Early mornings are best-fewer crowds, mist rising off the water, and the quiet hum of birds you won’t hear in the afternoon.

Why This Matters Beyond Beauty

These gardens aren’t just for tourists. They’re part of London’s identity. They show how a city that became the heart of an empire also became a leader in environmental thinking. The same people who built steam engines and factories also designed spaces to heal, reflect, and reconnect with the natural world.

Today, as cities struggle with climate change and mental health, these gardens offer lessons. They prove that nature doesn’t have to be tamed to be controlled-it can be guided, preserved, and made meaningful. They remind us that beauty isn’t accidental. It’s the result of intention, care, and long-term thinking.

When you walk through a London historic garden, you’re not just seeing plants. You’re walking through centuries of human imagination-shaped by hands that never saw a smartphone, yet built something that still moves us today.

Are London’s historic gardens open to the public?

Yes, most are. Kew Gardens, Hampton Court Palace Gardens, and St. James’s Park are fully open to visitors with free or ticketed entry. Some, like Chiswick House Gardens, require a small admission fee but offer free access to certain areas. Always check the official website before visiting, as some sections may be closed for restoration.

Which London garden is the oldest?

The Chelsea Physic Garden, founded in 1673, is London’s oldest botanical garden. It was originally created by the Apothecaries’ Society to grow medicinal plants. It still operates today as a working garden and educational site, with over 5,000 plant species.

Who were the most famous garden designers in London’s history?

Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown revolutionized garden design in the 18th century with his naturalistic landscapes. William Kent introduced the English landscape style at Chiswick House. John Nash redesigned St. James’s Park in the 1820s. And at Kew, Sir Joseph Banks and Sir William Hooker were key figures in turning it into a global center for botany.

Can I volunteer to help maintain these gardens?

Yes. Kew Gardens, Hampton Court, and Chiswick House all have active volunteer programs. Roles include planting, pruning, guiding visitors, and helping with historical research. No experience is needed-training is provided. Check their websites for opportunities.

Why are these gardens protected by law?

They’re protected because they represent irreplaceable cultural and historical value. Historic England lists them on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens, which means any changes-like building a new path or removing a tree-must be approved. This ensures their design, layout, and plant collections are preserved for future generations.

What to Do Next

If you’ve visited one of these gardens and want to go deeper, start with a book. The English Garden by John Harris and Michael Snodin gives a full history. Or pick up a guidebook from Kew’s shop-it’s packed with maps and plant histories.

Try visiting during a special event. Kew hosts night-time light trails in winter. Hampton Court has its annual Flower Show in July. Chiswick holds classical concerts under the trees in summer.

And if you’re feeling inspired, plant something in your own space-a rosemary bush, a climbing vine, a single tulip bulb. You don’t need acres to carry on the tradition. Just care, patience, and a sense of history.