Standing at the Greenwich Observatory, you’re not just looking at old telescopes and brass instruments-you’re standing on the line that divides the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. The Prime Meridian isn’t just a line drawn on a map. It’s a physical strip of brass embedded in the courtyard, and millions of people have stood on it, one foot in each hemisphere, just to say they did.

It’s easy to think of Greenwich as just another London tourist spot, like the London Eye or Tower Bridge. But this place changed how the world tells time. Before the 1884 International Meridian Conference, every town kept its own local time. Trains ran on different schedules. Ships got lost. The solution? Pick one line. And they picked this one-through the heart of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

Walking the Line: The Prime Meridian Experience

The moment you step into the observatory courtyard, you’ll see it: a thin, polished brass strip running through the stone floor. It’s marked with ‘Prime Meridian 0° Longitude’ in both English and French. You can stand with one foot in the Eastern Hemisphere and the other in the Western. Tourists take photos, kids hop back and forth, and locals smile like they’ve seen it a thousand times-because they have.

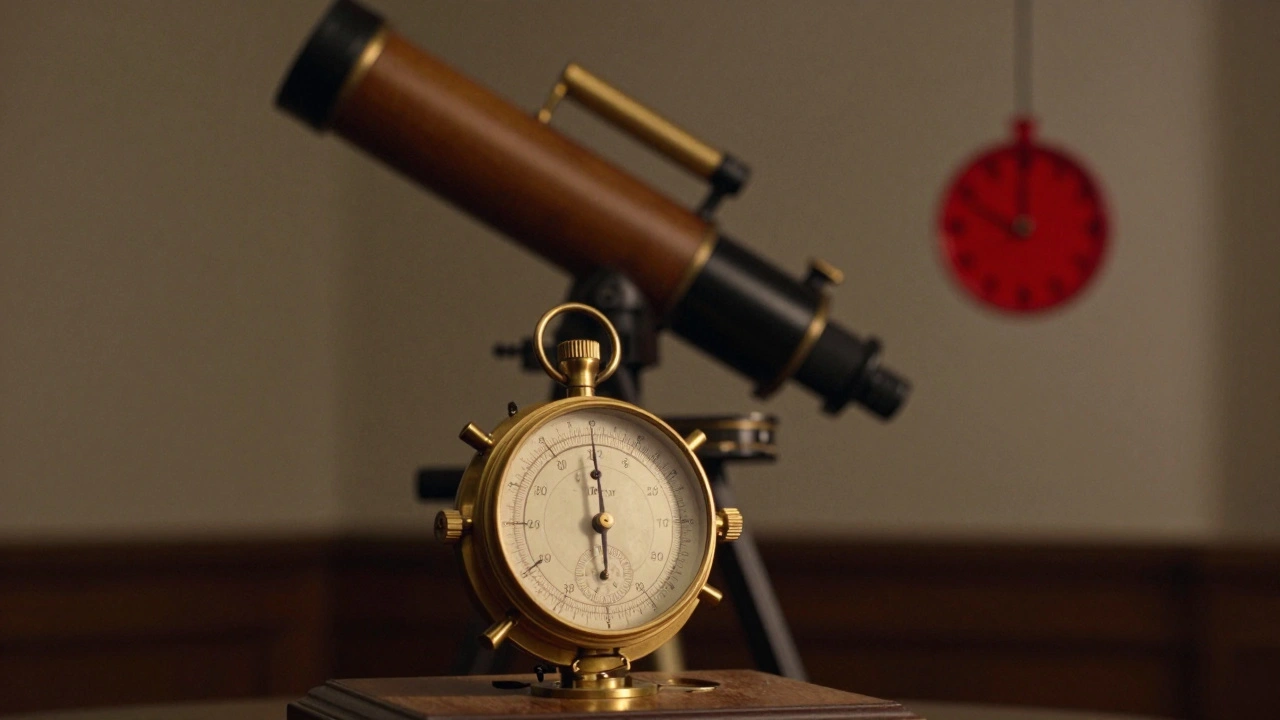

But here’s what most people don’t realize: the actual meridian line you’re standing on isn’t the original one. In 1851, the British built the Airy Transit Circle telescope to define the meridian. That telescope’s position became the official zero point. But modern GPS satellites later showed that the true zero line is about 102 meters east of where the brass strip sits. The brass line? It’s the historical marker-the one everyone knows, the one used on maps, the one that still counts.

You can’t touch the telescope itself-it’s behind glass-but you can peer through the viewing window. It’s not just a relic. It’s the reason we have Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), which became the world’s time standard. Even today, the UK’s official time is still set by the Royal Observatory’s atomic clocks, synced to the same system that began in 1884.

The Planetarium: A Journey Through the Stars

After walking the meridian, head inside to the Peter Harrison Planetarium. It’s not your average dome theater. This is one of the few planetariums in the UK with a full-dome digital projection system that can simulate the night sky with startling accuracy. You don’t just watch stars-you feel like you’re floating among them.

Shows change every few months, but typical programs include guided tours of the solar system, live views of the current night sky over London, and deep-space journeys to nebulae and galaxies. One recent show followed the path of the James Webb Space Telescope’s first images, showing how the universe looks in infrared light-something you can’t see with your eyes, but the planetarium makes real.

The dome seats 120 people, and shows run every 45 minutes. You don’t need to book in advance unless it’s a weekend or school holiday. Just show up 15 minutes early. The staff will let you sit in the front row if you’re curious about how the projection works. They’ll even explain how the system tracks real-time celestial positions using data from NASA and ESA satellites.

For kids, there’s a special 20-minute show called ‘The Story of the Sky’-simple, colorful, and full of animated constellations. Parents say it’s the first time their 6-year-old asked to go back to a museum.

What You’ll See Inside the Observatory Building

The Royal Observatory isn’t just about the meridian and the planetarium. The building itself is a museum of timekeeping and astronomy. The Great Equatorial Telescope, built in 1893, is still one of the largest in the UK. It’s mounted on a wooden frame that creaks when you turn it-just like it did when astronomers used it to track Mars and Jupiter over a century ago.

There’s also the Time Ball, a red sphere that drops every day at exactly 1 p.m. It was installed in 1833 to help ships on the River Thames set their marine chronometers. Back then, a ship’s captain would watch the ball drop from the dock, then adjust his clock. That one-second accuracy could mean the difference between reaching New York safely or crashing into rocks.

Don’t miss the Harrison Clocks. John Harrison spent 40 years building clocks that could keep perfect time at sea. His H4 chronometer, displayed here, solved the longitude problem. Before this, sailors had no reliable way to know where they were east or west. They’d guess. And they’d die. Harrison’s clocks changed that. The British Admiralty paid him £20,000 for it-equivalent to over £3 million today.

How to Plan Your Visit

Greenwich Observatory is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, which also includes the Cutty Sark and the National Maritime Museum. You can buy a combined ticket that covers all three. If you’re only doing the observatory and planetarium, the standalone ticket is £22 for adults, £11 for children, and free for under-fives. Members of the museum get in free.

It’s open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., with last entry at 4:15 p.m. The planetarium shows start every 45 minutes, so check the schedule when you arrive. Weekends get crowded, especially in summer. If you want quiet, go on a weekday morning.

Public transport is the easiest way. Take the DLR to Cutty Sark station-it’s a five-minute walk. Or take the Tube to Greenwich station (Zone 2) and walk uphill. The path is steep, but the views of the Thames make it worth it. There’s also a free shuttle bus from the Cutty Sark to the observatory if you’re tired.

Bring a jacket. Even in summer, it’s windy on the hill. And wear good shoes. The cobblestone paths and uneven steps aren’t kind to sandals.

Why This Matters Beyond the Tourist Photos

People come to Greenwich for the photos. But the real value is in understanding how one small observatory helped shape the modern world. Time zones? They exist because of this place. GPS? It still uses Greenwich as its reference point. Even your smartphone’s clock syncs to a time signal that traces back to this hill in southeast London.

It’s not just history. It’s living infrastructure. The same principles used to measure longitude in 1760 are still used to guide satellites today. The Royal Observatory doesn’t just preserve the past-it’s still part of how we navigate the world.

If you’ve ever wondered why we have 24 time zones, or why the world’s clocks start in London, this is where the answer begins. Not in a textbook. Not in a lecture. Right here, on this patch of grass, under the same stars sailors once charted by candlelight.

What’s Nearby

While you’re in Greenwich, don’t skip the National Maritime Museum next door. It’s free, and it’s packed with real artifacts-from Napoleon’s personal telescope to the uniforms worn by officers on the Titanic. The Cutty Sark, the last surviving tea clipper, is just a short walk down the hill. You can walk through its decks and smell the old wood.

For food, head to the market stalls along Greenwich High Road. Try the Jamaican patties or the fresh oysters from the Thames. There’s a coffee shop with a view of the river where locals go after their morning walk. No tourists. Just quiet, warm mugs and the sound of boats passing.

And if you’re there in December, the observatory grounds are lit up with Christmas lights. The planetarium runs a special holiday show: ‘A Winter Sky Over London.’ It’s the kind of thing you remember-not because it’s flashy, but because it feels like the stars are still watching.

Is the Prime Meridian line still used today?

Yes. Even though modern GPS places the true zero longitude about 102 meters east of the brass strip, the Greenwich Meridian remains the official reference for global timekeeping and mapping. All time zones are still calculated from Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), and GPS systems use it as their baseline for longitude.

Can you see the stars from the observatory?

Not really at night. The sky over London is too bright from city lights for serious stargazing. But the Peter Harrison Planetarium simulates the night sky with perfect accuracy. You’ll see stars, planets, and galaxies as they’d appear from Greenwich-without the light pollution.

How long should I spend at Greenwich Observatory?

Plan for at least two to three hours. One hour for the observatory exhibits, 45 minutes for a planetarium show, and another hour to walk the grounds, see the Time Ball, and explore the courtyard. If you’re also visiting the National Maritime Museum or Cutty Sark, add another hour or two.

Is it worth visiting with kids?

Absolutely. The planetarium’s kid-friendly shows, the chance to stand on the Prime Meridian, and the interactive time displays make it engaging for children. The Time Ball drops daily at 1 p.m.-kids love watching it fall. Many schools in London bring classes here for science field trips.

Do I need to book planetarium tickets in advance?

Not usually. Shows run every 45 minutes and tickets are sold on-site. But during holidays, weekends, or school breaks, it’s smart to book ahead online. You can reserve a seat for the planetarium when you buy your observatory ticket.

If you’re looking for a day trip that blends history, science, and a little wonder, Greenwich Observatory delivers. No gimmicks. No overpriced souvenirs. Just a quiet hilltop, a brass line, and the stars that still guide us.